Interview with Michael Farrelly, Tanzania Organic Agriculture Movement | May 2017

In East Africa, the space and terrain for Non-Governmental actors to operate and thrive keep constantly changing, mainly, for the worse. Recent political and economic developments in the region have seen the space for Civil Society to operate dwindling, doors for engaging governments and government officials being closed and even the very existence of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) coming under threat through various legislations which target the freedom of expression and the right to information.

Such a situation calls for urgent alternative ways of operating, engaging the government and other stakeholders and ensuring a sustainable future for the non-state sector in general.

To address some of those challenges and obstacles, the Tanzania Organic Agriculture Movement (TOAM) – one of RLS’ partners in the region, has recently embarked on establishing and running a Multi-Stakeholder Platform (MSP) on seeds in the country. RLS conducted an interview with Michael Farrelly, TOAM’s Programme Manager, to provide his insights about MSPs, TOAM’s experience in establishing and running the MSP, lessons learnt so far and if he thinks MSPs may be the new door that Civil Society actors may need to seriously consider as an alternative way of ensuring that they can still have access to other key stakeholders and engage them through such platforms.

What is an Multi Stakeholder Platform (MSP)?

An MSP is a decision-making body (voluntary or statutory) comprising different stakeholders who perceive the same resource management problem, realise their interdependence for solving it, and come together to agree on action strategies for solving the problem (Steins & Edwards, 1998). Multi-stakeholder platforms or hubs can systematically bring together companies, government, international organisations and civil society, align interests and support innovative collaborative action to achieve both business and development goals. Platforms may focus on a range of issues which require multi-sectoral action, for example, on tackling specific social issues (such as nutrition, education or health), creating new markets, developing sustainable value chains, supporting more inclusive business or addressing natural resource constraints. (The Partnering Initiative, Oxford, 2014)

What are the key elements of an effective MSP?

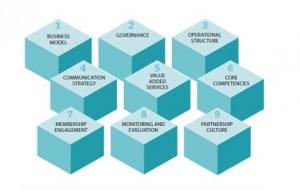

While we are still in the early stages of operating the MSP, according to The Partnering Initiative[1], there are 9 building blocks of an effective MSP.

Source: Reid, S., Hayes, J.P. and Stibbe, D.T., Platforms for Partnership: Emerging good practice to systematically engage business as a partner in development, The Partnering Initiative, Oxford, 2014

1 Sustainable Business Model: Every platform needs a strategy to achieve its purpose.

2 Governance: The actions of those managing the platform, allocating resources or selecting partnerships to support, must be accountable to all stakeholders within a clear system of rules.

3 Operational management structure: Building an effective platform institution requires the design of an appropriate and effective management structure to implement the platform’s tasks and produce its stated outputs.

4 Communication strategy: Good communication is vital to the success of all cooperation.

5 Value-added services: Platforms must offer well-defined and relevant services that provide significant value to members, partners and clients.

6 Core Competencies: Creating and catalysing new development partnerships, and providing services to them, all require a high level of competence in both the theory and practice of cross-sector partnering.

7 Membership engagement and management: Particularly in the early stages, the identification of platform champions can be an effective element in developing and retaining engagement from members and other external stakeholders.

8 Monitoring and Evaluation: Monitoring and evaluation of a platform for partnership should aim to focus on three main areas: the platform itself; the specific partnerships it brokers or supports; and the overall contribution to business and development goals.

9 Partnership culture: Just as with any partnership, a complex, multi-stakeholder platform requires a strong overall vision around which diverse sectors can mobilise, acknowledging that they will have different reasons for participation but can still develop common objectives, towards which they can work collectively.

I understand that TOAM has been in process to establish an MSP on Seeds in the country. What are the challenges that TOAM has encountered in the process of establishing the MSP so far? Any lessons learnt?

Farmers were initially lacking confidence in articulating their concerns. We dealt with this by first facilitating them to work in small groups - creating a safe space for them to share their concerns, by providing lobbying and advocacy training, and later by coaching individuals to develop and deliver presentations. This led to several articulate and passionate presentations being delivered by farmers in the presence of senior government officials.

Farmers were initially reluctant to engage with seed companies, fearing that their views would be attacked and flattened by aggressive and dismissive private sector lobbyists. We tackled this by organising the first two MSPs to be restricted to ‘like-minded’ actors from civil society, academia, and the government research community. This built farmers confidence and capacity to gradually accept the widening of MSP membership and participation.

Government officials were initially unsure about participating in the MSP. We dealt with this by organising a meeting with a selected group of Ministry of Agriculture officers to explain the MSP process and sensitise them to the importance of their participation. This led to strong and effective Ministry representation at the MSP.

Lessons learnt: While developing plans for the MSPs, we did some online research, and benefited from a IUCN / UKAid report on MSPs[2] which offered the following lessons:

- Communities need to have increased knowledge of their rights in order to be able to effectively engage in MSPs.

- Political elites have to be continually sensitized in order to induce the will for change and enable effective participatory decision‐making and knowledge‐

- Multi‐stakeholder platforms are the most successful when focusing on marginalized groups, for example indigenous peoples and especially women. Success in this context is seen as the ability of vulnerable and excluded communities to participate in decision making, to voice their demands, and to enhance their capacity to sustain engagement over time. The seed MSPs have been successful in this regard, through building the capacity of small-scale farmers, enabling them to speak truth to power, to be heard, and to have their demands and concerns acknowledged and taken seriously by officials with the power to make changes.

- MSPs can enable poor and marginalized people to have voice and influence policy making.

- The consolidation of MSPs is a medium to long-term process.

As a result:

- We facilitated MSP sessions on farmers rights;

- We established a practice of visiting and sensitising new stakeholder groups in advance of each MSP;

- We encouraged women farmers to be fully represented;

- We saw that the MSP events enabled farmers to make their case powerfully and effectively influence policy makers;

- We plan for medium to long-term engagement.

What have been the successes so far in TOAM’s processes to establish an MSP?

Farmers and seed producers empowered: In the project log frame the planned overall impact was that ‘Small scale farmers and seed producers are empowered to influence Government agriculture policy’. This was the key intended impact of the project. The project’s contribution to this impact has been very significant. The most important outcome of the project is that the Multi Stakeholder Seed Platform that the project has created and nurtured has now been adopted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries as the official seed stakeholder consultative body - the Seed Stakeholder Forum – under The Seed Act. The Multi Stakeholder Platform created during this project includes major representation by small-scale farmers and seed producers. This puts these key stakeholders in direct contact with policy makers, researchers, NGOs and other decision makers. It also gives farmers access to important documents such as policy drafts as well as information shared by other stakeholders. The project has also strengthened the capacity of smallholder farmers to present their challenges and issues clearly and convincingly to government. We held meetings with farmers /seed producers to discuss critical issues and support them to prepare and deliver presentations. Radio shows were broadcast, targeting farmer communities to ensure that the benefits of the MSP and wider project achievements are shared broadly with smallholder farmers and seed producers across the nation.

Linkages between stakeholders: The Seeds of Freedom project has created and strengthened linkages between stakeholders. By bringing stakeholders together in the three MSP meetings, the project has facilitated seed stakeholders to identify and position themselves among other stakeholders in the sector. The result of having closer ties between stakeholders is a more efficient and synchronised sector. By casting a wide net, the project has also encouraged stakeholders to identify with the sector who may have previously considered themselves to be on the fringe. Members include financial actors, media and officials from a range of government agencies.

Shared understanding on seed issues: Another impact of Seeds of Freedom has been the development of a shared understanding on seed issues amongst stakeholders. The seed platform offers a space for stakeholders to share their challenges and recommendations in discussions and presentations. Stakeholders bring their own issues to meetings but leave with a broader understanding of concerns and challenges faced by others. Although independent actors with different interests may not completely agree, we are starting to see more and more shared understanding.

Cohesion amongst seed sovereignty actors: Before Seeds of Freedom, several different NGOs were acting relatively independently through separate projects running in parallel with little interaction. These seed sovereignty actors were calling for similar things but with different voices and approaches. This project has created unison and cohesion between NGOs in the pursuit of seed sovereignty. ESAFF, MVIWATA and SAT have all joined hands with TOAM by engaging in the MSP. PELUM Tanzania saw the relevance of linking with this project and synchronised a key activity of their own project with our MSP3 meeting.

In the context of shrinking CSO Space in Tanzania and other East African Countries in general, what do you think would be the role of MSPs as an alternative Lobbying and Advocacy approach?

The shrinking CSO space in Tanzania and other countries in East Africa - whether related to a concentration of centralised power, or a reflection of a global shift towards more closed societies, or simply an underestimation of the importance of civil society – obliges civil society to find new ways of engaging in the policy arena. MSPs may offer such an alternative and can perhaps provide civil society with a new vehicle for policy advocacy. MSPs offer a range of benefits:

- The engagement of private sector and civil society is increasingly being recognised as an essential element of policy development;

- MSPs are being seen as the next generation of private public partnerships (PPPs) between government and the private sector;

- MSPs also bring civil society actors together regularly, offering opportunities to raise awareness, build capacity and strengthen coordination;

- MSPs can provide Government with a ready-made public consultation process; however the governance of MSPs must be carefully managed to ensure inclusivity. According to Reid et al 2014, the actions of those managing the platform, allocating resources or selecting partnerships to support, must be accountable to all stakeholders within a clear system of rules (which include conflict resolution mechanisms, which may arise due to the asymmetrical nature of the relations among participants). This is not only a basic requirement to demonstrate transparency but a practical means of monitoring actions and outcomes. An absence of good governance systems will undermine trust between participants and may increase the (already high) transaction costs involved in a multi-stakeholder platform. At the same time, it is important not to rush into too-rigid governance structures in the early development stages while the platform is engaging its core group of partners and co-developing its activities and approaches. It is also essential that governance structures can adapt and change as the platform itself adapts and iterates its approach when it begins to implement in earnest. [3]

- While the private sector is increasingly being given responsibility for service delivery, MSPs can enable civil society to keep tabs on private sector activity, and help to reduce negative impacts.

Would you recommend other CSOs to use MSPs for their advocacy engagements?

Yes, if the CSOs are prepared to work within the formal policy process, then MSPs provide a useful model for advocacy.

Your final comments about MSPs as channels for change in the society?

Perhaps we have been lucky, or in the right place at the right time, to see such a warm response from Government, which has agreed to take the Seed MSP on board as the official national consultative body on seeds. The challenge is now to consolidate that position, and develop a sustainable platform that is seen by Government and other stakeholders to add value to the policy process, and which avoids the risk of ticking a consultation box, but is taken seriously as a valued and beneficial partnership, with all major stakeholder groups on board, including government, farmers and the private sector. The Partnering Initiative asserts that MSPs “offer the potential for intensive, innovative and sustained collaboration from all sectors on issues that are integral both to national development plans and to a flourishing and sustainable private sector.” Yet they warn, “However, they are not an easy option. While they have great potential for impact, they require long-term stakeholder commitment, sustained resourcing and consistency of personnel to help ensure their success.”

Interview: Mussa Billegeya (RLS Programme Manager)

[1] Reid, S., Hayes, J.P. and Stibbe, D.T., Platforms for Partnership: Emerging good practice to systematically engage business as a partner in development, The Partnering Initiative, Oxford, 2014

[2] Surkin, J., (2011). Natural Resource Governance, Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: Learning from Practice. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

[3] Reid, S., Hayes, J.P. and Stibbe, D.T., Platforms for Partnership: Emerging good practice to systematically engage business as a partner in development, The Partnering Initiative, Oxford, 2014