AUTHORS

Amil Shivji, Hildegard Kiel

The African film industry is small, chronically underfunded, and most of its productions remain limited to the domestic market. Only rarely do African films make it onto the international film circuit, and even less often do they win critical acclaim from abroad, making their occasional success all the more remarkable.

Amil Shivji was born in Tanzania and is a lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam. He has written, directed, and produced short films that competed in the International Film Festival Rotterdam and the Pan-African Film and TV Festival of Ouagadougou, winning the People’s Choice Award in Zanzibar and Best Director in Africa. His feature directorial debut T-Junction (2017) opened the Zanzibar International Film Festival, where it won three awards. He has worked with the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation as a project partner since 2014.

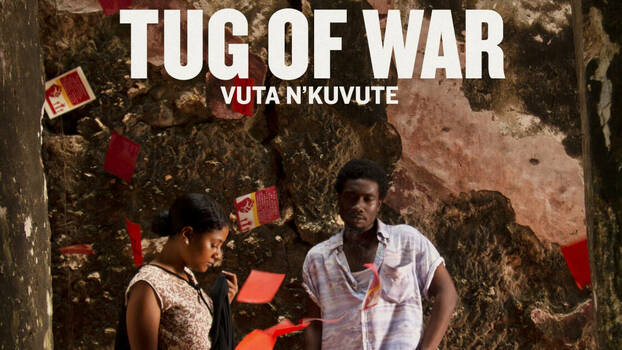

The new feature film Vuta N’Kuvute (Tug of War) from Tanzanian director Amil Shivji was the first-ever Tanzanian feature film to premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), which took place in mid-September, in the festival’s 46-year history. An adaptation of Adam Shafi’s award-winning Swahili novel of the same name, the film is set in 1950s Zanzibar in the final years of British colonial rule and revolves around the story of a dramatic romance, buffeted by the harsh waves of British rule and the local militant struggle for liberation.

Amil Shivji‘s latest work captures the unique historic tensions of an indelibly important time and space. Taking place less than a generation after the close of the East African slave trade, of which Zanzibar was a central hub, this period piece looks ahead to the end of half a century of colonial rule over the archipelago. Shafi’s renowned novel itself is taught in high schools across Tanzania, and now a new generation of lovers have Vuta N’Kuvute to inspire their dreams for better futures.

Described as an “anti-colonial In the Mood for Love”, Vuta N’Kuvute is not only one of the few films ever shot on the island of Zanzibar and the first Tanzanian feature film to appear at the festival, but also one of the first times the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation has sponsored the production of such a prominent feature film. In the run-up to its premier, Hildegard Kiel of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Africa Unit sat down with Shivji to learn more about his work and what he hopes the film will accomplish, both in Tanzania and internationally.

HK: Vuta N’Kuvute premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival as the first Tanzanian film in the festival’s history is a really big deal. What attracted you to Adam Shafi’s story in the first place, and what drove you to direct a film based on it?

AS: The first time I read the novel was in high school, it’s part of the curriculum in Tanzania, but I didn’t give it much thought. Then, when I was writing the script for T-Junction in 2016, I kept getting stuck. A conversation with my neighbour, who is also a teacher, made me think to draw from other works to break through my writer’s block. I started rereading the novel and didn’t put it down until I finished, because it is such amazing writing. It captures you.

As I read the novel, I could visualize it so easily. I met with the publishers in 2016 and optioned the book for two years. Two years later, after I had completed a draft of the story and realized what I liked about it along with things that I wanted to change, I felt confident enough to buy the rights and made changes to it that reflected my personal politics.

I imagine your film will bring the story to many more people than those who have already read the novel.

One of my primary goals for the film is to give Adam Shafi’s novel a second life. We have such fine Swahili literature. Tanzania, or even Zanzibar specifically, is the belly button of the Kiswahili language, and yet so much of this literature is dying out.

Of course, literature is dying across the globe, but that’s especially true for books in foreign languages that have not been translated, like Vuta N’Kuvute. We really have a dying culture. Considering that the novel is already taught in high schools in Tanzania, I hope the film will give it a rebirth and that the DVD will be used as teaching material in schools.

I hope to spark a new conversation on the development of film, because it’s a Tanzanian film with high production values, made by a Tanzanian team, that will be experienced and distributed in such early levels of education. This could help change the mentality and the ideology around arts in Tanzania. I think there is a real opportunity in different sectors, whether film and the arts, or even in politics and development studies, because we have never really talked about 1950s Zanzibar —it’s not in our history books. We were never behind the camera when all the colonial archiving and footage was being shot, meaning that our story was never told from our perspective on that period. It was a very contentious time, especially for Zanzibar, that ultimately led to the revolution.

The film is set in the last days of British rule in Tanzania. Tanzania was first colonized by Germany, and then by the British. The sixtieth anniversary of independence is coming up on 9 December. Do you think the story still has relevance today?

When I set about making the film, I was not interested in telling a story from the past. I wanted to tell a story that was very present. The way we made the film, the way the narrative unfolds, does not transport you to a place that is stuck in time. It takes you to Zanzibar of the 1950s in order to be able to reflect on Tanzania in 2021.

For me, that was very crucial because I wanted to create a discourse around a film set in an anti-colonial narrative that was nevertheless reflective of the oppressive systems we face today. Although we have overcome the colonial regime, we have not overcome oppression. Neo-colonialism and cultural imperialism have continued in many ways and forms. These conversations have not gone away.

How do we talk about it without blaming people or pointing fingers at foreigners? That is not the idea. The idea is to look at the current context and contemporary struggles that we have today in Zanzibar and Tanzania and see how we can step outside of the struggle and look at them and say, “Okay, that happened and continues to happen. We still have to resist. We still have to provide some kind of solution or respond to it.” That was the biggest idea behind telling this story.

The way I understand it, the film is very much connected to the struggles that need to happen or are happening at the moment.

Yes, Zanzibar especially has always gotten the short end of the stick—whether during colonial times, after colonialism, or even during the Union between the Zanzibar islands and mainland, Tanganyika. There are no debates about the relationship between the “big brother” mainland and the “little brother” island, and Zanzibaris are very much aware of this.

During our research phase, I realized that I was not making a film about a time that had passed, but rather about an ongoing struggle that started during that time but is ongoing. Simply put, it is about the resilience of the Zanzibari people. Zanzibar itself was a character in the film: how it has managed to respond and survive, to fight back all this time, regardless of who the adversary was.

Would you consider your movie to be a political movie?

Yes, I definitely think it is a political film. I have called it a coming-of-age love and political drama. The main themes, and I have tried to intertwine them, are love and revolution. I think there is love for revolution and there is revolution so that love can exist. They both escalate because those things are not mutually exclusive. The film’s characters Yasmin and Denge would not be able to fall in love in the context of oppression and colonialism. Not only because of the activity and the tension there was on the island, but also because the colonial regime implemented racial categories and racial segregation. Yasmin was an Indian woman and Denge was a black African man. Their relationship could not have thrived under colonialism. Their love itself was a revolutionary act, an anti-colonial act.

But in addition to that, they’re no strangers to the communal struggle. They are two lovers, being together, but there is also a community around them. All the people around them are also part and parcel of the struggle. They want to see the two friends’ love blossom. At the same time, how is it having a tangible and direct output against the colonial regime? Their love practically exacerbates the revolutionary spirit. It launches a wider movement and incorporates more people into what could have been seen as a very young, youthful, frivolous rebelliousness.

What is happening in Zanzibar today in terms of independence and in its relation to the mainland?

Zanzibar is a tourist destination. That advertising slogan has overrun Zanzibar’s entire history and culture. Now, that is not to say “no” to tourism. I understand its effect on the economy and the dollars it brings in. But at the same time, it should not come at the expense of the Zanzibari people and Zanzibari culture. That culture is not stagnant. Culture is not something that you write in a textbook and use for the rest of your life. That is the opposite of culture. Culture is ever-growing and ever-moving. The Zanzibari people are the ones who should define their culture, not anyone else. Not the government and not the tourism sector.

The people of Zanzibar have been resilient for a very long time: the Portuguese invasion, Arab colonization, the unequal relationship between the island and the mainland… We are talking about centuries of resilience—the people have defined their culture as resilience for a very long time because they are still there, they’re still living on the island, still pushing their ideas forward. I really wanted to capture that in the film.

Many of your films address these sort of intricate and interwoven layers of social class and cross-cultural references in Tanzanian society. How has the colonial and then the socialist past shaped the society of Tanzania and Zanzibar today?

Well, I can speak more to the Tanzanian mainland because I think Zanzibar had a very different route. Although we like to re-write history to say that there was this happy shaking of hands and everyone became one family, that is not what happened, and Zanzibaris will tell you that is not what happened. I think we are on two very different paths and one of the reasons why the Union happened was to bring those routes together.

The socialist path on the Tanzanian mainland really created a sense of unity. It brought us together with one language—Kiswahli—so that wherever you went in the country you could communicate with people, which also created a sense of building an economy together. Obviously, it had many flaws—after all, what system does not?—but I think at the very core of it, the philosophy and theory behind it was to implement a unified country. Let us not forget, before that came 150 years of colonial administration and governance which was not to the benefit of the people.

So how do you begin the birth of a new country? You have to deconstruct it and break down these very oppressive hierarchies that already exist. I think Julius Nyerere had a very interesting and progressive philosophy. Its implementation was not the best, but it brought people together and that was utterly crucial.

Zanzibar was a bit different, because Zanzibar was part of the Omani Sultanate, followed by the overthrow in early 1964—the revolution, where a lot of people were killed. The official figure I think is 600, but when you speak to people on the ground, it was likely over 10,000. We are talking about an area with 300,000 inhabitants, so it’s a really significant number.

After the revolution, there were never tribunals or reconciliation or forgiveness, so people haven’t been able to really talk about that period and that trauma has persisted. I think it has created intergenerational trauma that has been passed down from family to family, from father to son and from mother to daughter. It wasn’t that long ago—survivors of the revolution are still alive. That has really created a tension in Zanzibar, and whenever there are elections, whenever there’s a reminder that Zanzibar lacks the autonomy it deserves, it brings out this anger and frustration. That’s why it has resulted in violence every time.

In your previous film, Aisha, you took on the difficult subject of violence against women and how it is tolerated in Tanzania’s very patriarchal society. Your new film again features strong female characters who defy society’s expectations. How important is feminism and women’s liberation to your work, and who is your main influence in this regard?

Yes, it is obviously ironic and I guess a bit too mainstream as well, unfortunately, for men to take on these roles. As a director, producer, and writer in a very gender-biased industry like film, I have never consciously said that I am going to go tell a female story because that is what needs to be done. I just feel that I have been raised by very strong women, my mother and my sister, and it has been a no-brainer for me to have strong women characters in my stories. I have been surrounded by them my entire life. It was not a conscious choice to please NGOs.

When I was researching the story, one of the biggest struggles was giving the female characters more agency. I wanted the main character to be much more engaged with the political story, and not just be Denge’s lover who pushed him to be a better fighter. But the female characters on the side-lines in Shafi’s novel, who were not on the frontlines of the revolution, were also written beautifully. Their very existence was very much a metaphor for the resistance against colonialism and patriarchy.

One of our characters, Jasmin’s close friend Mwajuma, was modelled on Siti Binti Saad, the famous taraab singer from Zanzibar. She likes to drink and party and go out. Those very frivolous activities were a form of resistance for a woman in the 1950s in Zanzibar. At the same time, her music was used to express stories of the downtrodden, of the underprivileged, and that was a conscious political choice. That is what we would call “revolutionary songs against colonial regimes”—Mwajuma’s character really embodies that. Mwajuma started as a secondary character in the film, but in my opinion, she almost became one of the protagonists because she represents the Zanzibari people, or at least one part of it, the lumpenproletariat. She really represents the resilience and revolutionary spirit of the Zanzibari people.

Tanzania recently inaugurated its first female president. Has this given feminism a boost in the country?

I think having President Samia Suluhu come to power was, without a doubt, a ground-breaking move. Her swearing-in as president has led to a lot of positive conversations around the role of women in the political arena and in leadership roles. It was very exciting in the beginning when she filled her cabinet with women. But at the same time, let’s not forget she’s a politician, and the president of a country that has traditionally been very conservative. To expect her to overhaul the past five, ten years of a very patriarchal system and a very oppressive regime is unrealistic. The primary work, 99 percent of it, has to be done by the people themselves.

How did you manage to produce a feature-length film in a country with no sizable professional film industry? What obstacles did you have to overcome?

[Laughs] By God’s grace! It was and it still is an extremely ambitious project. We do not have an infrastructure or industry in Tanzania. We make Nollywood-style, straight-to-DVD, very poor films in this country and we make a lot of them, but films that meet international standards are few and far between.

When we started the project, my idea was to make a short proof of concept just to prove that it was doable, and then bring in a producer or support from foreign associations while keeping the story local. A producer I know quite well, Steven Markovitz, is responsible for some of the top cinema in the continent. Most recently he made the Kenyan film Rafiki, which was even screened at Cannes. He reached out to me and said he was very interested in the story. I had also already raised a significant amount of money from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. I think it impressed him that an independent producer in Tanzania was able to raise that kind of money. He loved my script and came on as a producer. We pulled together our resources to apply for international grants and get global recognition for the project.

During this phase I was quite adamant about having a local cast and crew as much as possible, which ended up being 95 percent of the team, and creating infrastructures so as not to be dependent on outsiders. We had offers from very prominent streaming platforms early on who said, “We love it, we want to take it on, but it has to be mostly in English.” Not only did I film it in Swahili, but I worked with elderly Zanzibari Qur’an teachers to create a language that would be accessible today but also represent how Swahili sounded in the 1950s. You have to be honest about the story, the culture, and the people. For me, the primary audience are the people who are going to watch the film in schools.

We were able to tell a story with international standards while keeping the team and content local. I held auditions in Zanzibar even though it would have been easier elsewhere, but I did it to create systems that Zanzibaris can keep working with. In many ways, if we had gone with the international industry’s wishes, it would have been easier. Keeping it local made it much tougher but it made it more honest and more dignified. It’s a battle that we started a long time ago and will continue even after this.

You mentioned that the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation was an early supporter of the film. What values do you have in common with the foundation and how are those reflected in your work?

The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation has supported my work for a very long time, and I do not know whether words can express my gratitude to the organization. I am not saying this as the typical sponsor message, I say this from a place of truth, because I have never reached a point—and hopefully never will—where there was a clash of ideas. There has always been a point where I have brought in my script, my story, my concept, and approached the foundation to see how they could support it, rather than the usual kind of relationship where an organization commissions you to work within their agenda.

Our collaboration began in 2014 with my short film Samaki Mchangani, which is about land grabbing, followed by T-Junction, which is about the different social classes within our societies. That led up to Vuta N’Kuvute, which is about communist struggles on the island of Zanzibar and general resistance to the present regime. The conceptualization of my stories has taken place in alignment with the foundation’s goals and mission on the African continent. It has been a refreshing and exciting experience, a real collaboration in the truest sense of the word. Besides the financial support, we had many discussions about the content and how to further push the implementation of these films, whether through distribution mechanisms, screenings in rural areas, or supporting the general ecosystem of filmmaking and film exhibition. After all, it’s not just an art form, but an educational tool for the people.